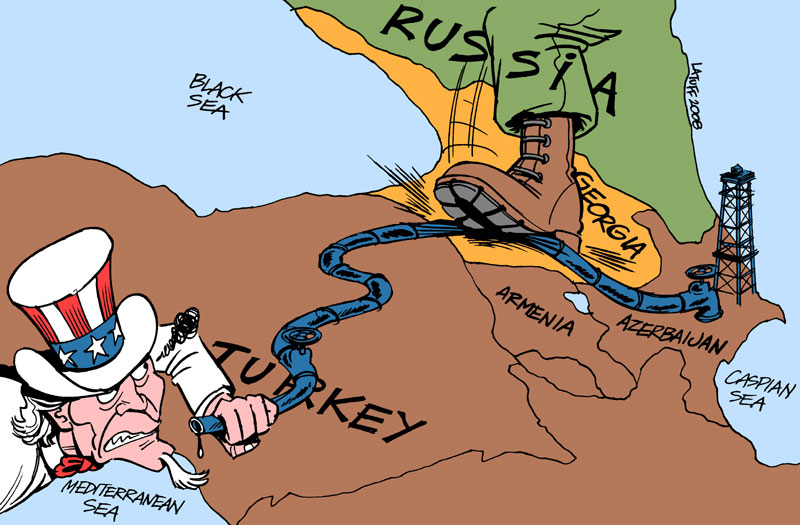

The paper following this commentary was produced by a Georgian national for the well known American think tank, Jamestown Foundation. The paper's main topic of concern is the new political realities of the energy transportation corridor of the south Caucasus in the aftermath of the Russian-Georgian war. The paper essentially discusses what I have been saying since the summer of 2008: The war between Russia and Georgia changed the geopolitical face of the Caucasus and has allowed Moscow to become the dominant power in the region as a result.

This topic is a crucially important political matter for us Armenians to comprehend in our attempt to better understand what is currently occurring between Ankara and Yerevan and in international relations in general. From an Armenian perspective, despite what the author of the paper would like us to believe, it can rightly be said that the political climate in the Caucasus today has changed in Armenia's favor. This change is essentially forcing Western powers as well as Turkey and Georgia to sit at the negotiating table with Yerevan. After years of ignoring and by-passing Armenia with all their regional projects, now they miraculously want to hear what Yerevan has to say about regional matters. Just recently, immediately following Mr. Sargsyan's successful visit to Georgia, authorities in Tbilisi announced the opening of their border with Russia, a vital trade route for Yerevan which had been closed for the past four years. As expected, Saakashvili, a "political corpse" now, has been made to heel in front of his victorious Armenian counterpart. I personally think Saakashvili's time as president is running out.

Gradually Moscow is preparing its playing field in the south Caucasus, and I am glad to report that Armenia today is a major player in their game. With whirlwind tours of Moscow, London, Paris and Tbilisi, Mr. Sargsyan has enjoyed a series of significant diplomatic successes as of late. And the most recent success was the official recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Sweden's parliament (see article at the bottom of this page). The action taken by Stockholm is in essence the continuing punishment of Turkey for turning away from its military run secular government. Under Erdogan's leadership Ankara has been moving towards Islam and relations between Ankara and Tel Aviv have been at an all time low. As a result, Ankara is being punished. Since Washington can’t afford to do it directly, it is allowing other governments to send the message instead. Spain may be next to send a message.

Nothing is left to chance in war and politics. I believe that what we are currently seeing today was planned some time ago and may very well be directly connected to the signing of the protocols between Yerevan and Ankara late last year. It is my opinion that Ankara and Tbilisi will eventually be brought down to their knees, barring any drastic unforeseen changes in the region's political landscape. Needless to say, Sargsyan’s administration has been playing a brilliant game of diplomacy. Those who were stubbornly insisting that the signing of the protocols late last year hindered the "Hat Dat" and opened the gates of hell must be/should be feeling very foolish at this point...

Arevordi

This topic is a crucially important political matter for us Armenians to comprehend in our attempt to better understand what is currently occurring between Ankara and Yerevan and in international relations in general. From an Armenian perspective, despite what the author of the paper would like us to believe, it can rightly be said that the political climate in the Caucasus today has changed in Armenia's favor. This change is essentially forcing Western powers as well as Turkey and Georgia to sit at the negotiating table with Yerevan. After years of ignoring and by-passing Armenia with all their regional projects, now they miraculously want to hear what Yerevan has to say about regional matters. Just recently, immediately following Mr. Sargsyan's successful visit to Georgia, authorities in Tbilisi announced the opening of their border with Russia, a vital trade route for Yerevan which had been closed for the past four years. As expected, Saakashvili, a "political corpse" now, has been made to heel in front of his victorious Armenian counterpart. I personally think Saakashvili's time as president is running out.

Gradually Moscow is preparing its playing field in the south Caucasus, and I am glad to report that Armenia today is a major player in their game. With whirlwind tours of Moscow, London, Paris and Tbilisi, Mr. Sargsyan has enjoyed a series of significant diplomatic successes as of late. And the most recent success was the official recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Sweden's parliament (see article at the bottom of this page). The action taken by Stockholm is in essence the continuing punishment of Turkey for turning away from its military run secular government. Under Erdogan's leadership Ankara has been moving towards Islam and relations between Ankara and Tel Aviv have been at an all time low. As a result, Ankara is being punished. Since Washington can’t afford to do it directly, it is allowing other governments to send the message instead. Spain may be next to send a message.

Nothing is left to chance in war and politics. I believe that what we are currently seeing today was planned some time ago and may very well be directly connected to the signing of the protocols between Yerevan and Ankara late last year. It is my opinion that Ankara and Tbilisi will eventually be brought down to their knees, barring any drastic unforeseen changes in the region's political landscape. Needless to say, Sargsyan’s administration has been playing a brilliant game of diplomacy. Those who were stubbornly insisting that the signing of the protocols late last year hindered the "Hat Dat" and opened the gates of hell must be/should be feeling very foolish at this point...

Arevordi

***

The Impact of the Russia-Georgia War on the South Caucasus Transportation Corridor

Executive Summary

The August 2008 war in the Caucasus revealed the new strategic realities that have emerged in the Black Sea / Caspian Region in recent years. These realities have been driven by overly ambitious Russian policies and have weakened Western strategic interests in the region. The conditions created immediately after the war appeared more favorable to Russia and less favorable to other nations in the region, most notably Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Ukraine.

But the world economic crisis and its impact on Russia, as well as the Russia-Ukraine gas dispute in January 2009, have diminished Russia’s gains and further damaged Russia’s reputation as a reliable energy supplier to Europe. In the long run, Russia may face very serious problems of separatism on its own territory due to Russia’s recognition of the breakaway provinces of Georgia. Given these uncertainties, it may be natural to expect that there will be stronger drive to get away from: 1) dependency on Russian energy in Europe; and 2) dependency on Russian transit infrastructure in Caspian /Central Asia region. In the long run, that may be reflected by Russia’s weakened strategic position in Europe and Central Asia.

The August war in Georgia demonstrated some risks associated with the functioning of the transit energy corridor in the southern Caucasus. It also demonstrated the need for broader security guarantees for a region that is vital to European and global energy security. The most important finding of the paper is that while the corridor has a tremendous potential to augment its transit capabilities with new pipelines, railroads, marine and air ports, the security of the South Caucasus transportation corridor cannot be taken for granted. Moreover, Western countries will need to ensure stability and security in the region in order for the corridor to meet its full potential.

The Russian invasion of Georgia established new strategic realities in Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia. It was the culmination of Russia’s impressive comeback in Eastern-European and Central-Eurasian affairs that has occurred in response to high energy prices, a weak US strategic position, European division and uncertainty in Turkey’s strategies. The war made clear that Russia is willing to use force to deepen and promote its interests, while western powers are not. This fact was predictable, but not certain to some. The war in Georgia helped firmly establish this reality and may also indicate that even NATO members may not be fully protected by their commitment to that organization. As the Russia-Georgia conflict demonstrates, military force has once again become a major factor in Russian foreign policy. Nevertheless, economic provisions and energy incentives are still the primary tools employed by Russia to further its foreign policy interests abroad.

At the same time, the weak Western response to Russia actions may send the wrong signal to the Russian leadership about the level of freedom it has to use force in what Russia considers its sphere of influence. Furthermore, the weak economy and the declining popularity of Russian leaders may create internal instability within Russia and tempt Russian leaders to once again utilize force to further their objectives. Europe and the United States need to carefully consider their policy response to such scenarios.

Another major finding of this paper is that energy is an important factor in the stability of any country and, in Georgia’s case, domestic energy security is also the foundation for stability of transit, and development of the entire regional infrastructure. The physical damage to the infrastructure and the environment in Georgia as a result of the war was tangible but not large. The damage to Georgia’s transportation system is repairable in a relatively short period of time. The pipelines are gradually approaching pre-conflict volumes of the oil and natural gas shipments although the shipments via railway, ports, and air have all shown signs of decline. Instead, the key problem emerged with the malfunctioning of the largest energy facility in the country - the Enguri hydro power plant.

The reservoir for the power plant is located on Georgian-controlled territory while the actual electricity production plant is located on Abkhaz/Russian controlled territory. The Georgian leadership had to make a very difficult political decision in accepting the offer of the Russian company Inter RAO (the subsidiary of the giant Russian state-owned energy monopoly Inter RAO United Energy Systems (UES)) on joint operation of the power plant. While there is a positive history of activities of the Inter RAO UES in Georgia, the Russian state-owned company’s control of a key electricity supplier for the entire country is not the best political and economic security outcome for Georgia.

Lastly, the paper argues that the initial damage that the war inflicted upon the political reliability of the transit corridor is gradually diminishing and that new opportunities are emerging. The complete reversal of this damage can be possible but will depend on U.S. and EU policy, the role of Turkey, internal stability in the Caucasus region, and Russian policy in Central Asia and the Caucasus. It is important to remember that when the initial decision to revitalize the energy corridor through Georgia and Azerbaijan was made in the mid 1990s, the security environment was extremely difficult and there was no infrastructure to support shipment of oil through the corridor, yet leadership of the United States and Turkey supported that decision and helped to implement it. Today’s environment is much more favorable considering the functioning infrastructure and greater demand for Caspian energy.

New natural gas discoveries in Turkmenistan and the next stage in oil and gas developments in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan will require additional export capacity and a tough battle is ahead between the different export options, each supported by state sponsors with competing interests. It is significant in this context that Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan signed an agreement on November 14, 2008, to develop a Trans-Caspian oil transportation that will include onshore oil pipeline in Kazakhstan and a tanker fleet in the Caspian Sea to ship Kazakh oil to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and on to the world markets. As it was indicated at the Budapest summit devoted to the Nabucco pipeline project on January 27, significant progress has been made on the development of a natural gas link between the Caspian and Europe, and Georgia has an important role to play.

These developments indicate that the energy producing countries of the region are determined to seek the diversification of export options, but they need to be supported by the United States, and in particular European, NATO, or Turkish security guarantees. After all, Western Europe and Turkey are the major consumers and beneficiaries of Caspian energy resources.

But the world economic crisis and its impact on Russia, as well as the Russia-Ukraine gas dispute in January 2009, have diminished Russia’s gains and further damaged Russia’s reputation as a reliable energy supplier to Europe. In the long run, Russia may face very serious problems of separatism on its own territory due to Russia’s recognition of the breakaway provinces of Georgia. Given these uncertainties, it may be natural to expect that there will be stronger drive to get away from: 1) dependency on Russian energy in Europe; and 2) dependency on Russian transit infrastructure in Caspian /Central Asia region. In the long run, that may be reflected by Russia’s weakened strategic position in Europe and Central Asia.

The August war in Georgia demonstrated some risks associated with the functioning of the transit energy corridor in the southern Caucasus. It also demonstrated the need for broader security guarantees for a region that is vital to European and global energy security. The most important finding of the paper is that while the corridor has a tremendous potential to augment its transit capabilities with new pipelines, railroads, marine and air ports, the security of the South Caucasus transportation corridor cannot be taken for granted. Moreover, Western countries will need to ensure stability and security in the region in order for the corridor to meet its full potential.

The Russian invasion of Georgia established new strategic realities in Eastern Europe and Central Eurasia. It was the culmination of Russia’s impressive comeback in Eastern-European and Central-Eurasian affairs that has occurred in response to high energy prices, a weak US strategic position, European division and uncertainty in Turkey’s strategies. The war made clear that Russia is willing to use force to deepen and promote its interests, while western powers are not. This fact was predictable, but not certain to some. The war in Georgia helped firmly establish this reality and may also indicate that even NATO members may not be fully protected by their commitment to that organization. As the Russia-Georgia conflict demonstrates, military force has once again become a major factor in Russian foreign policy. Nevertheless, economic provisions and energy incentives are still the primary tools employed by Russia to further its foreign policy interests abroad.

At the same time, the weak Western response to Russia actions may send the wrong signal to the Russian leadership about the level of freedom it has to use force in what Russia considers its sphere of influence. Furthermore, the weak economy and the declining popularity of Russian leaders may create internal instability within Russia and tempt Russian leaders to once again utilize force to further their objectives. Europe and the United States need to carefully consider their policy response to such scenarios.

Another major finding of this paper is that energy is an important factor in the stability of any country and, in Georgia’s case, domestic energy security is also the foundation for stability of transit, and development of the entire regional infrastructure. The physical damage to the infrastructure and the environment in Georgia as a result of the war was tangible but not large. The damage to Georgia’s transportation system is repairable in a relatively short period of time. The pipelines are gradually approaching pre-conflict volumes of the oil and natural gas shipments although the shipments via railway, ports, and air have all shown signs of decline. Instead, the key problem emerged with the malfunctioning of the largest energy facility in the country - the Enguri hydro power plant.

The reservoir for the power plant is located on Georgian-controlled territory while the actual electricity production plant is located on Abkhaz/Russian controlled territory. The Georgian leadership had to make a very difficult political decision in accepting the offer of the Russian company Inter RAO (the subsidiary of the giant Russian state-owned energy monopoly Inter RAO United Energy Systems (UES)) on joint operation of the power plant. While there is a positive history of activities of the Inter RAO UES in Georgia, the Russian state-owned company’s control of a key electricity supplier for the entire country is not the best political and economic security outcome for Georgia.

Lastly, the paper argues that the initial damage that the war inflicted upon the political reliability of the transit corridor is gradually diminishing and that new opportunities are emerging. The complete reversal of this damage can be possible but will depend on U.S. and EU policy, the role of Turkey, internal stability in the Caucasus region, and Russian policy in Central Asia and the Caucasus. It is important to remember that when the initial decision to revitalize the energy corridor through Georgia and Azerbaijan was made in the mid 1990s, the security environment was extremely difficult and there was no infrastructure to support shipment of oil through the corridor, yet leadership of the United States and Turkey supported that decision and helped to implement it. Today’s environment is much more favorable considering the functioning infrastructure and greater demand for Caspian energy.

New natural gas discoveries in Turkmenistan and the next stage in oil and gas developments in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan will require additional export capacity and a tough battle is ahead between the different export options, each supported by state sponsors with competing interests. It is significant in this context that Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan signed an agreement on November 14, 2008, to develop a Trans-Caspian oil transportation that will include onshore oil pipeline in Kazakhstan and a tanker fleet in the Caspian Sea to ship Kazakh oil to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and on to the world markets. As it was indicated at the Budapest summit devoted to the Nabucco pipeline project on January 27, significant progress has been made on the development of a natural gas link between the Caspian and Europe, and Georgia has an important role to play.

These developments indicate that the energy producing countries of the region are determined to seek the diversification of export options, but they need to be supported by the United States, and in particular European, NATO, or Turkish security guarantees. After all, Western Europe and Turkey are the major consumers and beneficiaries of Caspian energy resources.

Source: http://www.jamestown.org/programs/recentreports/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=34654&tx_ttnews[backPid]=7&cHash=54b53bf6cc

|

Nabucco Project Stalemated, European Expert States

Gas is a geopolitical instrument now, so the purpose of a higher gas price for Turkey may be to remind the country of something, Alexander Rar, a European energy expert for CIS, stated in his interview with 1news.az, commenting on the rise in the price for Azerbaijani gas supplied to Turkey. “The gas price always has political implications, especially when each one seeks its ‘niche’ in a pipe,” Rar said. As regards the Nabucco project, the expert said it has been stalemated, “as Russia has been able to successfully persuade a number of Balkan states into joining the South Stream project.” Rar pointed out that Turkey and Russia are successfully negotiating the South Stream project, the Ukrainian leadership has undergone changes as well, so “this transport corridor is getting interesting.” According to the expert, hardly any gas is available for Nabucco – Turkmenistan sells its gas either to Russia or to China, so it is only Azerbaijan, which is selling a great amount of gas to Russia and Iran, that can supply gas to the Nabucco pipeline. “The West hopes that the Nabucco pipeline can be filled with Iranian gas. But the situation is not stable there, and it remains to be seen whether a sufficient amount of gas will be supplied to the European market. But this is the only chance for Nabucco,” Rar said.

Source: http://news.am/en/news/russia/15128.html

Russia-Georgia Crossing Reopens

Russia and Georgia have reopened a border crossing that has been closed since July 2006, officials say, reports BBC. The Verkhny Lars crossing - situated on a narrow mountain pass high in the Caucasus mountains - was closed by Russia amid deteriorating relations. It is the only crossing that does not go through the Russian-backed breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Georgian forces were driven out of the two regions in a bitter war with Russia in August 2008. Diplomatic relations between the two have not been restored since the war.

No warming

The agreement to open the crossing came after a request from landlocked Armenia. The crossing was once an important point on a vital trade route, says the BBC's Tom Esslemont at the border. Now that it is open again it brings Georgia and Russia physically closer, but not politically, our correspondent adds. Georgia says the opening does not signify a warming of ties between the two countries. Georgian export goods are still under a Russian embargo. Relations between the Georgian and Russian leaders, meanwhile, remain sharply antagonistic. If this unceremonious opening is of benefit to anyone it is to Georgia's neighbour Armenia, which is landlocked and whose economy is suffering one of the sharpest declines in growth in the former Soviet Union.

Source: http://armenianow.com/news/21309/upper_lars_reopens

No warming

The agreement to open the crossing came after a request from landlocked Armenia. The crossing was once an important point on a vital trade route, says the BBC's Tom Esslemont at the border. Now that it is open again it brings Georgia and Russia physically closer, but not politically, our correspondent adds. Georgia says the opening does not signify a warming of ties between the two countries. Georgian export goods are still under a Russian embargo. Relations between the Georgian and Russian leaders, meanwhile, remain sharply antagonistic. If this unceremonious opening is of benefit to anyone it is to Georgia's neighbour Armenia, which is landlocked and whose economy is suffering one of the sharpest declines in growth in the former Soviet Union.

Source: http://armenianow.com/news/21309/upper_lars_reopens

No comments:

Post a Comment

Dear reader,

New blog commentaries will henceforth be posted on an irregular basis. The comment board however will continue to be moderated on a regular basis. You are therefore welcome to post your comments and ideas.

I have come to see the Russian nation as the last front on earth against the scourges of Westernization, Americanization, Globalism, Zionism, Islamic extremism and pan-Turkism. I have also come to see Russia as the last hope humanity has for the preservation of classical western/European civilization, ethnic cultures, Apostolic Christianity and the concept of traditional nation-state. Needless to say, an alliance with Russia is Armenia's only hope for survival in a dangerous place like the south Caucasus. These sobering realizations compelled me to create this blog in 2010. This blog quickly became one of the very few voices in the vastness of Cyberia that dared to preach about the dangers of Globalism and the Anglo-American-Jewish alliance, and the only voice emphasizing the crucial importance of Armenia's close ties to the Russian nation. Today, no man and no political party is capable of driving a wedge between Armenia and Russia. Anglo-American-Jewish and Turkish agenda in Armenia will not succeed. I feel satisfied knowing that at least on a subatomic level I have had a hand in this outcome.

To limit clutter in the comments section, I kindly ask all participants of this blog to please keep comments coherent and strictly relevant to the featured topic of discussion. Moreover, please realize that when there are several "anonymous" visitors posting comments simultaneously, it becomes very confusing (not to mention annoying) trying to figure out who is who and who said what. Therefore, if you are here to engage in conversation, make an observation, express an idea or simply insult me, I ask you to at least use a moniker to identify yourself. Moreover, please appreciate the fact that I have put an enormous amount of information into this blog. In my opinion, most of my blog commentaries and articles, some going back ten-plus years, are in varying degrees relevant to this day and will remain so for a long time to come. Commentaries and articles found in this blog can therefore be revisited by longtime readers and new comers alike. I therefore ask the reader to treat this blog as a historical record and a depository of important information relating to Eurasian geopolitics, Russian-Armenian relations and humanity's historic fight against the evils of Globalism and Westernization.

Thank you as always for reading.