How

the Russian-Georgian War Has Changed the World - Interview with Paul Goble

| |

|

On the second anniversary of the Russian-Georgian war Yulia Savchenko talked about the consequences of confrontation and conflict lessons with Paul Goble - political scientist, a former specialist on ethnic minorities the U.S. State Department, and now a researcher with the Diplomatic Academy of Azerbaijan.

Yulia Savchenko: This is the second anniversary of the Georgian-Russian conflict of 2008. Different people have taken different things from this conflict. What do you think Georgia has learned from the conflict?

Paul Goble: Different people in Georgia have learned different lessons. Many, except perhaps the president, understand why the conflict happened. On the eve of the fighting, he clearly showed that he had misinterpreted the rules of the game in the international arena as well as misinterpreted remarks of the US President and Secretary of State. He interpreted their statements that the US always supports its friends as meaning he could do whatever he pleased. Since that time, he has used the threatening posture of Russia to distract attention and silence his opponents. Whatever else, Georgia in the future needs to show more creativity in dealing with the new environment than it did earlier. Others have learned from the conflict. Russia’s neighbors now can see that Moscow is not constrained in showing who is the boss in the region even to the point of using force. No one thought that was the case, but now these countries have no guarantee that it won’thappen again. This has changed their perception of their own defensive needs and of Russia more generally. That is only one of the ways Russia suffered as a result of the war. While Vladimir Putin and his team have proclaimed their victory, many Russians recognize that his decision was ill-conceived as well The Russian army did not do well, with poorly trained soldiers shooting at each other. As a result, Russia does not look as strong as it did. Instead, it looks like a weak bully. That is a very dangerous situation for any country to be in.

JS: And what this conflict has taught the United States?

PG: The US certainly has learned a few things. Perhaps first of all, we have had the lesson driven home that when we deal with other countries, we must always be sure that our statements are not misinterpreted. Clearly Saakashvili heard things from Washington that Washington did not in the end intend. U.S. policymakers need to be clear about what the US will and won’t do, regardless of a desire to show oneself supportive and friendly. Another lesson I hope we have learned is that Moscow today is not prepared to live by the rules. To go forward, Russia will have to work hard to reassure the US and others that it will behave as countries are supposed to.

JS: Two years ago, after the clash between Russia and Georgia, you testified that you support the principle of national self-determination. Do you think the Obama administration will follow this advice, especially in the wake of the International Court’s decision on Kosovo?

PG: I believe in the right of nations to self-determination. I believe that Abkhazia has demonstrated its ability to translate this right into reality. The situation regarding South Ossetia is much more problematic both because of the existence of North Ossetia, its own relations with the Russian Federation, and its geographic position as a kind of dagger aimed at Tbilisi. In many respects, the step that would most disturb Moscow would be if the West and the US in particular were to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Imagine what it would mean if 27 NATO members had embassies in Sukhumi. That would open the question of the recognition of republics now north of the Russian Federation border. I do not exclude such a development. It would be more interesting if Georgia has recognized Abkhazia. Abkhazians, of course, would likely seek to find a way to prevent that if only because of the obvious undesirable consequences for Moscow. Consequently, it won’t happen soon. But if these states remain recognized only by a few states, this will be the beginning of an era in which there may be many partially recognized states. Thinking ahead to the tenth anniversary of the conflict, I hope that at that time we will be able to discuss this crisis more soberly with fewer comments about Russian aggression, more foreign embassies in Abkhazia. I don’t know whether an American one will be among them, but some kind of reconciliation of all parties is likely, if only because living in a world where all past crimes are constantly at the center of attention is so very difficult.

Source: VOA News (Russian)

The Georgia War and its consequences, by Alexander Rahr

Putin and Medvedev had just settled into their new political leadership roles. The whole world remained in expectation of a new impulse towards modernization in Russia by the liberal Medvedev. The West decided to postpone the plan of greater NATO expansion to the East, keeping Ukraine and Georgia on the waiting list. In Poland and the Czech Republic the opposition against the US missile defence system had increased. Washington and Moscow were not arguing about the Iranian Nuclear program any more. Medvedev promised Ukraine that mafia structures should be destroyed and that gas business should get more transparent. The US presidential campaign had begun and it seemed that Obama, the candidate of the Democratic Party, planned new peace initiatives towards Russia. Poland and Lithuania put a veto on negotiations, concerning a new partnership agreement between the EU and Russia. Analysts were speaking about a new era of thaw characterizing the relationship between Russia and the West.

But then everything occured very fast. Over the night of August 7th/8th

2008, during the opening of the Olympics Games in China, a new war in

the Caucasus started. The world was shocked. Instead of sporting

competitions, the main attention of all the news was devoted to rolling

tanks, to waves of refugees, and to bombed cities and the many dead.

Nobody could believe it: the small Georgian “David” provoked

(challenged) the Russian “Goliath”. Parallel to the war events, a

propaganda battle was sparked by all the sides to an extent never seen

before. At that point, it was not clear what exactly was happening on

the south side of the Caucasian mountains. The information was

confusing and contradictory. Who was the offender? Who was the victim?

Were there several truths?

The fact is that there had been a

running conflict on the border of the Georgian heartland and the

breakaway republic of South Ossetia for many years. Since the civil war

between Georgia and South Ossetia in 1991-2, there had been both

Russian and Georgian troops along the border. However, Russia was not

seen as playing the role of an honest mediator, adding fuel to the

conflict by issuing Russian passports to the inhabitants of the

breakaway republic. In addition, Russia was charged with letting the

Ossetians arm themselves to the teeth and shell Georgian peace-keeping

troops and neighbouring Georgian villages unhindered. The north of

South Ossetia is actually isolated from Russia by the Caucasian

Mountains. However, there exists the so-called Roki tunnel, which was

hewn out of the mountains about 50 years ago. The tunnel is the main

economic supply-route from Russia to the breakaway republic. Georgia

considers the self-proclaimed government of South Ossetia to be a

smuggler regime. On the horror night of August 7th-8th, the Roki tunnel played a decisive role for the outcome of the war.

On the pretext of protecting the

Georgian villages from shelling by South Ossetian guerrillas

(irregulars), on this night Saakashvili attacked South Ossetia. With

his blessing, 12,000 armed men, upgraded with western and Israeli

military equipment, were deployed into the breakaway republic. At 22:00

the ceasefire between the Georgian Blue Berets and the Ossetians was

broken. The line of the Russian peacekeepers was overrun, and many Blue

helmets were killed. The capital of South Ossetia, Tskhinvali, came

under fire. The plan of Saakashvili was to drive out the Ossetian

population via the Roki tunnel to North Ossetia, one of the Russian

republics in the North Caucasus. The Georgians were hoping that the

mass exodus of the refugees via the Roki tunnel would prevent the

Russian military advancing from the other side.

Georgia committed a mistake crucial for

the outcome of the war. Obviously, Saakashvili did not expect such a

quick reaction from Russia or resistance from the Ossetian partisans,

although he was probably informed via satellite about the Russian troop

movements in the north. But, at the same time, Putin was at the opening

of the Olympic Games in Beijing. Medvedev seemed not to have things

under control. Tbilisi believed it would be possible to set a quick

precedent in South Ossetia. But Russia has already evacuated several

hundred civilians via the Roki tunnel to North Ossetia one week before,

a fact of which Saakashvili could not have been aware.

The Kremlin found itself in a dilemma:

either give up South Ossetia and risk losing power status in the

region, or fend off the attack. Twelve hours after the Georgian attack,

Moscow sent tanks of the 58th army through the Roki tunnel

into Georgia. The main aim of this action was to support the South

Ossetian irregulars against the Georgian regular troops. Russia would

speak later of an attempted genocide against the Ossetian population.

Georgia would accuse Russia of provoking the war, shelling Georgian

villages from South Ossetia. Analysts disagreed as to whether

Saakashvili fell into a trap set by Moscow or if he decided in favour

of a blitzkrieg, expecting support form the West. Both sides had enough

reasons to escalate the conflict in such a manner in order to solve

their “strategic task” in the region.

Around midnight, Georgian troops

occupied Tskhinvali. Thousands of civilians fled via the Roki Tunnel

(in the opposite direction to the moving Russian tanks) into Russia.

According to Russian information sources, during that night almost 2000

civilians became victims of the Georgian aggression. Later, Western

sources will argue that the number of victims was far smaller. The

international human rights organization, Human Rights Watch, reported

that Georgian troops used cluster bombs against the civilian

population. The Georgian side asserted that Russian air raids had

destroyed Tskhinvali. In any case, the Georgian forces maintained their

defence line for some time. On August 9, Russia brought in its Air

Force. According to rumours, Putin threatened Saakashvili, in case of

continuing resistance, to bomb Tbilisi. The Russian Navy sailed from

Sevastopol in order to control the Abkhazian Coast. No further doubts

persisted. The world was witnessing a new war. After many hours of

fighting for Tskhinvali and heavy losses on the Georgian side (people

talked about 4,000 dead Georgian soldiers), Saakashvili announced the

retreat in the afternoon of August 8. His coup had failed. His

well-trained and equipped army had underestimated the reaction of the

Russians. The biggest part of the Georgian military equipment was

destroyed.

In a mad rush, Georgia pulled her army

back. As a consequence, the Russian troops pushed forward, a step that

would be later criticized by western media as disproportionate. The

Russian Air Force destroyed within a few hours the major part of the

Georgian military infrastructure. The radar tower in Tbilisi, the oil

terminal in the port of Poti as well as the military garrison in Gori

were bombed. Television pictures of Saakashvili lying on the ground,

escaping an imaginary Russian air strike, flashed around the world. In

spite of the fact that Georgian air defences were able to shoot down

two Russian fighter-bombers, the Russian army already controlled the

whole northern part of Georgia by the end of August 10. The vanguard of

the Russian offensive was formed from special units of former Chechen

guerrillas, who had been considered by Moscow only a few years before

as terrorists. They seized the Georgian city of Gori under the battle

cry “Allah is great”. The Georgian population escaped to the southern

parts of Tbilisi. Georgia and Russia accused each other of conducting

ethnic cleansing. In the part occupied by Russia, there took place

looting by the Ossetian guerrillas, and revenge on the Georgian

civilian population.

Russia continued to destroy Georgian

military installations, justifying it as revenge for the death of the

Russian Blue helmets and Russian citizens in the South Ossetia. In

reality, Georgia was to be rendered incapable of conducting future

attacks against South Ossetia. In addition, Russia wanted to prevent

Georgia from becoming a front-line NATO state on its southern doorstep.

Suddenly, a second front was opened. The other breakaway republic,

Abkhazia, seized the historical opportunity finally to separate from

the Georgian heartland. As in South Ossetia, there had been previous

skirmishes between Abkhazians and the Georgian military. The Abkhazian

separatists kicked the Georgian army units out of their strategic

positions in the mountains around Abkhazia. The Russian Black Sea Fleet

provided essential protection from naval attacks.

The new Caucasian war ended after only

three days. But the real battle in the international media and

diplomatic arena was only just beginning. And in this battle Russia

seemed to be losing, experiencing difficulties explaining her position

and her “truth” concerning the reasons and the course of the war to an

angry western public. In the eyes of most Westerners, Georgia was a

small choir-boy and Russia the aggressor. The Western media almost

exclusively reported on Georgian civilian casualties and damage; only

rarely did the fate of the Ossetians get a hearing.

On the other hand, people in the west,

particularly from former Warsaw Pact countries were reminded of the

events of the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and

Afghanistan in 1979. Suddenly, fear spread of a Russian attack on the

former Soviet republics. Some Western media stoked the fear by talking

about a neo-imperialist Russia. The presidents of Poland, Ukraine and

of three Baltic states gathered for a solidarity demonstration for

Saakashvili in Tbilisi. They wanted to help their ally to rewrite

history and to present Russia as the single aggressor in this conflict.

The United States supported this anti-Russian rhetoric and castigated

the “imperialist war against Georgia” by Moscow. Between the U.S. and

Poland the long-pending agreement on the stationing of a missile

defence systems was signed. At the signing ceremony, it was made clear

that this defence system was not only pointed against states like Iran.

Moscow was expected to understand the message. Due to American

pressure, the NATO-Russia Council was put on ice.

Meanwhile, the EU Council and the

French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, hurried to Moscow to prepare a

ceasefire and a peace agreement. But just before Sarkozy arrived in

Moscow, president Medvedev declared an end to the military operation

against Georgia. The course of the negotiations between the EU and

Russia was extremely complicated. Russia refused to recognize in the

Peace Treaty the sovereignty of the Georgian state, including two

breakaway republics. Medvedev also demanded the recognition of a

“protected zone” for the Russian Peace troops along the border between

Abkhazia/South Ossetia and the Georgian heartland. Sarkozy, who wanted

to stop the war as soon as possible, gave his approval. How wide this

buffer zone within Georgian heartland should be was not a subject of

the negotiations. The French spoke later about “a few kilometres”,

where the Russian Blue helmets are allowed. Russia expanded this zone

unabashedly almost upto the Black Sea coast.

After the war, it became impossible to

force the Abkhazians and the Ossetians to rejoin Georgia, either in the

short or medium term. However, for the West the recognition of the

state sovereignty of the breakaway republics was out of question,

especially, after such blatant International Law violations by Moscow.

The French foreign minister referred to the war as a return to the

middle Ages. The astonishment of the international community was,

however, incomprehensible. The conflict had been there for all to see.

But the EU seemed to be always taken by surprise by events in Eastern

Europe. The attention of the EU was only fixed on the colour

revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, on the gas dispute between Ukraine

and Russia, as well as on Russia resuming a position of power.

Obviously, the Western community had

prematurely put the disintegration of the Soviet Union on the shelf.

The post-Soviet states and regimes often evolved (with western

participation) into fragile states. Numerous territorial and ethnic

conflicts still persisted in a frozen state. In the Caucasus alone many

of these potential conflicts came to the fore. Some reasons for these

latent conflicts across the post-Soviet space were caused by the

transitional process of the 90s as well as by external geopolitical

factors. One of the conflict issues was the expansion of NATO,

supported by the United States, to the Black Sea Region and competition

for the raw material reserves of the Caspian Sea.

Foreign observers debate why the war

broke out when it did? Experts of all camps try to interpret the

dynamic of the events and to develop different explanations of the

conflict. The central question is who has started the war?

Saakashvili denies having ordered the attack on Tskinvali. Russia

claims the opposite. In an interview for CNN, Putin blamed conservative

circles in America for having an interest in provoking the war. Putin

underlined that it was done in order to improve the chances of the

ex-presidential candidate of the Republican Party John McCain, who

refers to Moscow as the new imperialist aggressor. Also the disaster of

the Iraq war needed to be cloaked in a shroud. President Bush, on his

way out of office, desperately needed a success in foreign policy in

order not to be painted by history as a complete loser. His Secretary

of State, Condoleezza Rice, was fighting like a lioness to improve the

diplomatic legacy of the Bush administration.

A legitimate question is whether the

numerous American and Israeli advisors of Saakashvili knew about his

planned attack? According to the newspapers “Frankfurter Allgemeine

Zeitung” and “Moscow Times”, the United States gave Georgia in the

preceding five years 200 million dollars as military aid. Additionally

the Georgian army received 100 Mio U.S. dollars from Turkey; Israel

provided Georgia with a modern air force. With regard to precision

weapons, night vision devices and modern communication equipment, the

Georgian army was better equipped than the Russian before the conflict.

According to one version, American consultants of Saakashvili advised

him against the attack on South Ossetia but failed to persuade their

political pupil.

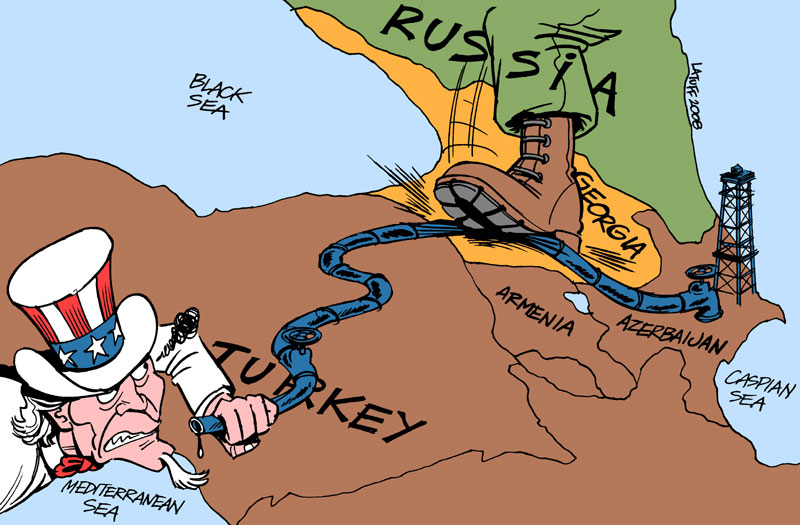

Supposedly, Russia successfully also

used the aggression of the hot headed Saakashvili to achieve other

strategic objectives in the geopolitically sensitive region. First of

all, it weakened the role of Georgia as an exclusive transit corridor

for oil and gas from the Caspian Sea, by-passing Russia. As long as

Iran is demonised as a rogue state by the United States and remains

isolated, the transport of the energy sources from Central Asia and

Azerbaijan, by-passing Russia, is manageable only via the territory of

Georgia. At the end of the 90s, the former Soviet oil pipeline had been

reactivated from Baku to the Georgian Black Sea coast. In the middle of

this decade, a second pipeline from Baku via Georgia to the Turkish

Mediterranean port of Ceyhan has been laid. Both pipelines brought to

an end the Russian monopoly for oil transport to the West.

Secondly, the war destroyed the chances

of Georgia entering NATO. If it turns out that Saakashvili really

planned the attack on South Ossetia and a quick reunification with the

breakaway republics to increase his membership chances, the doors to

the western military alliance will stay closed for him. As is

well-known, NATO accepts only territorially consolidated states into

its ranks. NATO does not want to interfere into the territorial or

ethnic conflicts in a candidate country, primarily in order to avoid

any possibility of a World War. However, President Bush promised

Saakashvili NATO membership in the nearest future. Did the head of the

Georgian state just want to use this “window of opportunity” in the

last month of the George Bush presidency to utilise the conflict to

slip into NATO via the back door? It is an incredible but coherent

hypothesis.

Thirdly, Russia’s reaction was revenge

for all the humiliations at the hands of the West after the Soviet

Union disintegrated. On this hypothesis, Georgia paid for Kosovo, for

three NATO expansions to the East, for the U.S missile defence system

and for much more. Therefore, according to the Russian point of view,

the unilateral recognition of Abkhazia and South Osssetia is coherent.

After all, it was the West which reconstructed the Balkans according to

its own preference and breached international law into the bargain. At

that time, Russia had no other choice than to watch it happening. But,

Putin and Medvedev turned the tables and played the same card. Now, the

West is watching Moscow arranging the Caucasus according to its own preference, even if it is breaching international law in doing so.

Russia’s changed attitude is of course

problematic. Till now, Moscow insisted that existing international law

should be based on the fundamental principle of the territorial

sovereignty of a state. This argument Moscow deploys in its fight

against Chechen separatists. The preservation of Russia as a state

stands above the question of human rights. The same argument Russia

used in her critique of the recognition of the Serbian province of

Kosovo by the West. The Serbian president, Slobodan Milosevic, had the

right from the Russia’s point of view, to fight with Albanian terrorism

on his own territory. But now, in the case of Abkhazia and South

Ossetia, Moscow has quickly adopted the Western argument. Moscow argues

that the protection of human rights in South Ossetia takes priority

over the principle of the state sovereignty of Georgia. But it is not

only Russia which has problems with justification. Suddenly, the West

interpreted the conflict in Georgia against its own principles,

principles which not long before were so vehemently defended in the

case of Kosovo. Everyone bends international law to suit vested

interests.

The new EU and NATO member states are

convinced they are right. They have always warned of a new imperialist

Russia and referred to the reconciliation policy of the “old Europeans”

towards Russia as naïve and strategically wrong. Although this position

was supported by the Bush administration, in Europe, nevertheless, the

collective prevails. How should Russia punished as demanded by Poland

and the Baltic States? Should Western universities kick out all Russian

students as the president of Estonia proposed? Or, as in the case of

Belarus, should the West impose a travel ban on Russian politicians?

Should the EU freeze the bank accounts of the Russian oligarchs, such

as the president of Chelsea football club, Roman Abramovich? In any

case, the “new Europeans” demand that NATO and the EU expand control

instruments against Russia. There is a “Cold War” reappearing on the

direct borders between EU and Russia.

The call for the immediate

inclusion of Georgia and Ukraine into NATO is getting louder and

louder. Sometimes it seems that the recent members of the Warsaw Pact

want to prevent the historical reunification of the whole European

continent, including Russia. For the Eastern Europeans, Russia in all

respects will always be the aggressor. The people there are convinced

that, if the West does nothing, Russia could soon invade the Crimea and

the Baltic states. There is no doubt in Warsaw, Tallinn and Riga that

the conflict in Georgia is only the beginning of a Russian offensive

violently to restore its lost empire.

In reality, the West is helpless and

powerless. Firstly, the West is deeply split on the Russian question.

Germany, France and other states cannot unilaterally take the side of

Georgia in order to stay credible in the conflict, especially when

Saakashvili`s responsibility causing the conflict is there for all to

see. Within the EU two extreme positions are colliding with each other.

The Italians, led by Putin’s friend, Silvio Berlusconi, call for

avoiding any condemnation of Russia and simply getting back to everyday

problems. The Poles present the toughest position and bring in their

old agenda of energy and NATO back into the discussion. Suddenly,

everybody is talking about a new “Berlin Wall” which should be built

around the Caucasus in order to prevent new aggression from Russian

Imperialism.

The German and French call upon all

sides in the Georgian conflict to compromise. The Cold War rhetoric is

obnoxious. At an extraordinary summit on September 1st, 2008

the EU finally decided against sanctions against Russia and gave Moscow

tree months to withdraw the rest of the troops form the Georgian core

land. The West needs Moscow´s cooperation on the Iranian question, in

the Middle East, in climate protection, on the issues of

non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and finally in

space-exploration. For security reasons, the EU has postponed the hasty

inclusion of Georgia and Ukraine into NATO. After Saakshvili provoked

the conflict with Russia, the immediate acceptance of Georgia into NATO

would be a signal for others to start new conflicts with Moscow in

order to follow the Georgian way into NATO. However, the EU has broken

off the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with Russia for the time

being. Objectively, this fact cannot damage Moscow so much. Russia is

not interested in a relationship with the EU on the basis of those

outdated rules. Russia feels strong again and superior to the

Europeans, at least militarily and partly economically.

The influential industrial lobbies in

the countries of the “old EU”, most notably Germany and Italy, but also

France, Spain, Belgium, Netherlands, Austria advise their governments

not to get into confrontation with Moscow. The economic links with

Russia are so advanced now that, in the case of indiscriminate

sanctions against Moscow, the West will cut off its own nose. One

should just examine the trade volumes of the individual EU countries

with Russia to realize that the big western companies make use of all

segments of the Russian market today. Russia produces very little in

her own country. Starting from machinery, industrial technologies, food

products, luxury goods and, not least, financial credits are all

imported form the West. Thousands of jobs in Germany and other EU

countries are directly dependent on the growing Russian market.

The dialogue channels to Moscow should

not be closed; on the other hand, Russia must be persuaded to leave

Georgian territories. First, the EU tries to be active and to raise

money for the reconstruction of Georgia. What should a concrete plan

for Georgia look like? Neither breakaway province can be forced to join

Georgia again, just as Kosovo Albanians could not be part of Serbia

anymore. But the West should also not accept the Russian annexation,

because it can only awaken the further appetite of Russia, for example,

for the Crimea. Could a confederation be a golden solution for the

Georgian problems? Three states in one, as in the case of Bosnia and

Herzegovina? Had the odd EU enough power in foreign policy to be able

to help stabilize the South Caucasus, such a Stability Pact might have

been developed years ago. The Europeans lack the will to realise this

plan. Recently, the EU, under the leadership of Germany, launched a

Central Asia initiative. Should it be now revisited for the South

Caucasus? On the other hand, the EU would have to divert significant

resources from the Balkans in order to stabilize the Caucasus.

Along with setting up social and

economic infrastructures in Georgia, the EU could make an important

contribution to the strengthening of the democratic and constitutional

institutions in the Caucasian republic. Instead of an accretion to

NATO, the EU should offer Georgia the perspective of EU entry. The

Georgian accession to the EU could be realised only if Turkey also

received membership in the European economics and community values. The

Stability Pact should also take into consideration the other conflict

zones in the region.

The frozen conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh could

develop into the next major conflict in the tinderbox of the Caucasus.

Just as Saakashvili equipped his army in order to fight the breakaway

provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the Azeri leader Ilham Aliev

considers it to be his patriotic duty to drive from this territory away

even by force the Armenians who conquered the Azeri province of

Nagorno-Karabakh 15 years ago. The target policy of the EU towards

South Caucasus should also be to bring out a historic reconciliation

between Turkey and Armenia. The still-closed border between Turkey and

Armenia is an obstacle for the European security and defence policy in

the region, which could be part of Europe one day.

Moscow should have placed the emergency

over the sovereignty of both provinces within the hands of

international law. In order to consider this independence legal, one

should have carried out local referendums, as well as the

internalization of the conflict, by the construction of OSCE and UN

monitoring bodies. The presence of international peacekeeping forces is

also required. There are few appropriate models, but there are the

precedents already applied in the Balkan conflict. The Russian side has

the following explanation: Georgia with the support of the USA plans

new attacks on the breakaway republics. These last two could be

defended only with Russian military support. The Russian peacekeeping

troops are not enough to act as a deterrent. Putin also points to the

presence of American warships cruising along the eastern Black sea

coast.

Perhaps, it would be advisable for the

West to start negotiations with Medvedev and Putin about a new OSCE, as

was done before with the Soviets, and to establish coexistence with

Russia on the continent on the basis of a set of common purposes.

Hence, Medvedev’s proposal to work together with the EU, envisaging a

collective construction of Europe, is quite realistic. Even if the West

fights against giving Russia a voice or a right of veto in the

construction of 21st century Europe, it will take some

years, but, afterwards, the idea of Russian membership of NATO will win

more and more supporters among the Russian and Western politicians.

NATO expansion to the East is the biggest obstacle in the relationship

between Russia and the West. The West is only partly right, when it

proclaims that each country has a right to join any military alliance

and Moscow cannot prevent it.

However, one of the main principles of

the European policy after the Cold war is that the security of one

state cannot be ensured at the expense of the safety of another. NATO

can hardly ignore the fact that Russia feels threatened when there is

Western military infrastructure directly on her borders. The today NATO

can theoretically in the next few years integrate all the former Warsaw

Pact countries as well as new independent states on post-Soviet

territory. NATO partnerships with all these countries have existed for

two decades. But Russia also needs a membership perspective, even if it

will be never realized. The invitation for Russia to join NATO will

help to reduce potential conflicts between her and other potential

candidates. As a start, integration could be stared with cooperation on

missile defence. This defence system should protect not only America

and Poland, but also the West and Russia together.

Russia's Geopolitical Scales in the Caucasus, by Sergey Markedonov

The

latest Caucasian cycle of presidential visits to the South Caucasus

ended 2-3 September. During those days Dmitriy Medvedev visited Baku,

capital of Azerbaijan. And although this visit of his was of

significance in its own right (determining the prospects for

Russian-Azerbaijani bilateral relations), it is expedient to analyze

its results in a comparative context, bearing in mind the results of

the Russian head of state's Yerevan trip (19-20 August this year). It

cannot be said that the Russian president's latest Armenian-Azerbaijani

cycle brought revolutionary changes to the South Caucasus. However,

some bright touches were added to the new geopolitical landscape.

Combining Dmitriy Medvedev's two visits into a single Caucasian cycle

does not seem to us to be a mere journalistic metaphor. There are

several reasons for this. And they are not only and indeed not chiefly

to do with Armenia and Azerbaijan.

|

|

|

After August 2008 Russia and Georgia

diverged to opposite sides of the barricades. It could of course be

said that in the conditions of the 21st century the total isolation of

two countries from each other is impossible (and more important,

unreal). However, the fact remains that despite the preservation (and

even consolidation) of Russian business positions in Georgia, political

contacts between the two countries amount merely to the Geneva talks

format, enabling each of the two diplomatic communities to monitor the

other side's position from time to time. If, indeed, you do not count

visits by (celebrity) Kseniya Sobchak or Mikhail Gorbachev (accompanied

by other influential retirees) as serious political contacts.

Incidentally, the visits to Moscow by (former Georgian Prime Minister)

Zurab Nogaideli and (former parliament speaker) Nino Burjanadze can

also hardly be perceived as anything other than PR operations. On 26

August 2008, by recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Moscow made its

choice concerning the prospects for relations with Georgia. However,

there are finer points here. Tbilisi made its choice four years earlier

by beginning to "unfreeze the conflicts."

Be that as it may,

Moscow has no serious levers of influence on Georgia. And none can be

foreseen in the immediate future. In military terms Russia's potential

is many times greater than Georgia's, but it is not Moscow's aim to

annihilate Georgia's "sovereign democracy." And indeed the realization

of this idea would encounter more serious resistance from the key world

players than was the case two years ago. At the same time it is

extremely important for the Russian Federation to preserve its

influence in the South Caucasus, in view of the multifaceted links

between that part of the region and the North Caucasus. Hence the

heightened attention paid to contacts with Yerevan and Baku. The loss

of one of these partners would have serious consequences for Russia,

since in that event two out of the three entities recognized by the

world community would be following an anti-Russian (at the very least,

none too benevolent) course. But the snag is that Russia's two

potential partners in the Caucasus are in a relationship of

confrontation with each other. And although war has not been formally

declared between them, there are no diplomatic relations and the

Karabakh conflict is perceived in both Armenia and Azerbaijan as a

military-political standoff, and moreover one that has key significance

for the two states' political identities. Nagorno-Karabakh, to use

images from the Middle East story, is not the "Territories" or the

"Strip." It is Jerusalem. And the conflicting sides are not only

conducting a regional arms race and information warfare but a fierce

struggle for external support. In this respect Moscow is a very

important resource for both Baku and Yerevan. It is therefore no

accident that in the summer of 2010 both Armenian and Azerbaijani

political experts were in no hurry to comment on the August accords

between Moscow and Yerevan, preferring to wait for September' s signals

from Dmitriy Medvedev in Baku. Thus, Russian diplomacy faces a

difficult task -- not to allow itself to be drawn into this race and

not to turn into a player in this confrontation. We have seen that it

is not uncommon for strong powers to become dogs wagged by the tail --

we have seen it in the case of Russia with Chechnya, Abkhazia, and

South Ossetia, and also in the story of American-Georgian relations and

relations between Washington and Pristina. Medvedev's new Caucasus

cycle has shown that, thus far, Moscow is succeeding in solving this

dialectical puzzle. At the beginning of September 2010 the

Armenian-Azerbaijani geopolitical scales were balanced.

I

immediately foresee objections. Moscow prolonged the presence of its

based on Armenian territory (thereby sending a signal to Baku that a

violent solution is not acceptable to it), while Azerbaijan did not

receive any tangible military-political "carrots." It cannot be 100%

ruled out that something like that will appear, in order to bring the

scales into balance. However, no such thing has emerged from the

results of the Russian leader's visit to Baku. For our part we consider

this line of argument superficial. In September 2010 Azerbaijan gained

something that is no less important than tanks and guns. For the first

time in its post-Soviet history it resolved the problem of delimitation

and demarcation of the border with a neighboring state. This problem

has not yet been resolved with any of the other neighboring countries.

With Armenia, Azerbaijan has not so much a border as a front line. And

even the Nakhichevan sector, which is much quieter than the "line of

contact" in Nagorno-Karabakh, is closed and resembles a bristling

border. In the course of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict Armenian forces,

occupying five districts neighboring on Karabakh entirely and two

partially, took control of the former USSR border with Iran on the

River Araks. And despite the positive trend in relations between Tehran

and Baku the border between these two countries is a serious headache

for Azerbaijani politicians (taking into account the growing ambitions

of the Islamic Republic as a regional superpower).

Relations

between Georgia and Azerbaijan are reminiscent of a "honeymoon," but

the position of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Kvemo Kartli also creates

considerable problems in bilateral relations between Baku and Tbilisi.

As for the sea border that Azerbaijan shares with Turkmenistan in the

Caspian, here too everything is very confused. For years now the two

republics have been arguing about the oil and gas deposits in the

Caspian Sea. In the summer of 2009 official Ashgabat even announced its

intention of appealing to the International Court of Arbitration to

uphold its rights to disputed fields.

The problem of

delimitation and demarcation with Russia was also difficult to resolve.

Talks on defining the 390-km state border had been going on for years,

but in 14 years (beginning in 1996) the question had not found a

positive solution. From time to time the sides clashed over the problem

of dividing the water resources of the River Samur. There was

discussion of the legal status of the border villages of Khrakhob and

Uryanob. In 1954 these two villages in Azerbaijan's Khachmazskiy Rayon

were temporarily transferred to the Dagestani ASSR (Autonomous Soviet

Socialist Republic) as pasture land, and 30 years later the Council of

Ministers of the Azerbaijani SSR (Soviet Socialist Republic) extended

the term of the previous document by a further 20 years (to 2004).

The

breakup of the USSR led to major adjustments to the economic plans of

the "party and government." The situation was made more acute by the

fact that the inhabitants were ethnic Lezgins, who also inhabit

Dagestan. By the beginning of the 2000s many of them had acquired

Russian passports. After August 2008 there was much speculation in the

media on the subject of a repetition of the South Ossetian story in

Azerbaijan. Today all this idle theorizi ng and speculation is left to

the historians. Russia has become the first country after the breakup

of the Soviet Union to sign a treaty with Azerbaijan on borders. The

presence in the Russian delegation of important officials responsible

for administration in the North Caucasus (Aleksandr Khloponin,

Yunus-Bek Yevkurov) indicates that Moscow is also positioning the

agreement with Baku as being advantageous to itself. The Dagestan

sector of the Russian border today requires serious (and more

importantly, effective) cooperation with the southern neighbor.

But what did Moscow demand in exchange?

Not

very much, in fact. It is more a question of rhetoric. The Russian

president, while in Baku, stated that he personally (and Russian

diplomacy in implementation of the state's position) is interested in

the peaceful resolution of the Karabakh conflict. Moscow is prepared to

continue to perform a mediation mission to seek compromise solutions.

The signal has been sent, so to speak. Following on from the Yerevan

protocol, the Kremlin is trying to draw the attention of its

Azerbaijani partners to the fact that the Russian Federation is

interested in any solution to the conflict except a military one. But

is Russia capable of fully controlling its interests? The answer to

that question would most likely be negative.

Undoubtedly some

hot heads (both in Baku and in Yerevan) will be cooled by Moscow's

position. But then other considerations come into force, which even the

staunchest admirers of the Kremlin in Armenia and Azerbaijan cannot

ignore. Any Caucasian leader must resort to "patriotic rhetoric" in

order to maintain his legitimacy. This becomes particularly relevant on

the eve of elections (in Azerbaijan the parliamentary campaign is

already gathering pace).

Therefore a resumption of military

rhetoric cannot be ruled out. And this is not because politicians in

Baku are more bloodthirsty. The loss of Karabakh is a national trauma

that nobody is yet prepared to heal. And mentioning it makes it

possible to maintain one's popularity. Thus, Russia's role in both

Azerbaijan and Armenia should not be overestimated. However, the fact

that Moscow is trying to play on several boards at once and attempting

to pursue a balanced and pragmatic policy must be gratifying.

Particularly in the context of other none too successful initiatives.

It would be good if an awareness of geopolitical diversity as a

necessary component of foreign policy would also penetrate other

segments of Russian diplomacy.

|